World Teachers’ Day

Tributes to teachers from Roy Cheng Tsung and Maureen Murphy Woodcock.

TRANSCRIPT

On October 5, 1966, UNESCO and the International Labor Organization ratified a recommendation for professionalizing education: the rights and responsibilities of teachers and standards for their initial preparation and further education, recruitment, employment, and teaching and learning conditions. October 5 continues to be celebrated as World Teachers’ Day. It celebrates the importance of teachers, but it also recognizes the support they need to do the job in the classroom. UNESCO, by the way, is the United Nations organization that promotes cooperation in education, science, culture and communication to foster peace worldwide.

In honor of World Teachers’ Day—and in honor of teachers, two tributes to teachers from Passager.

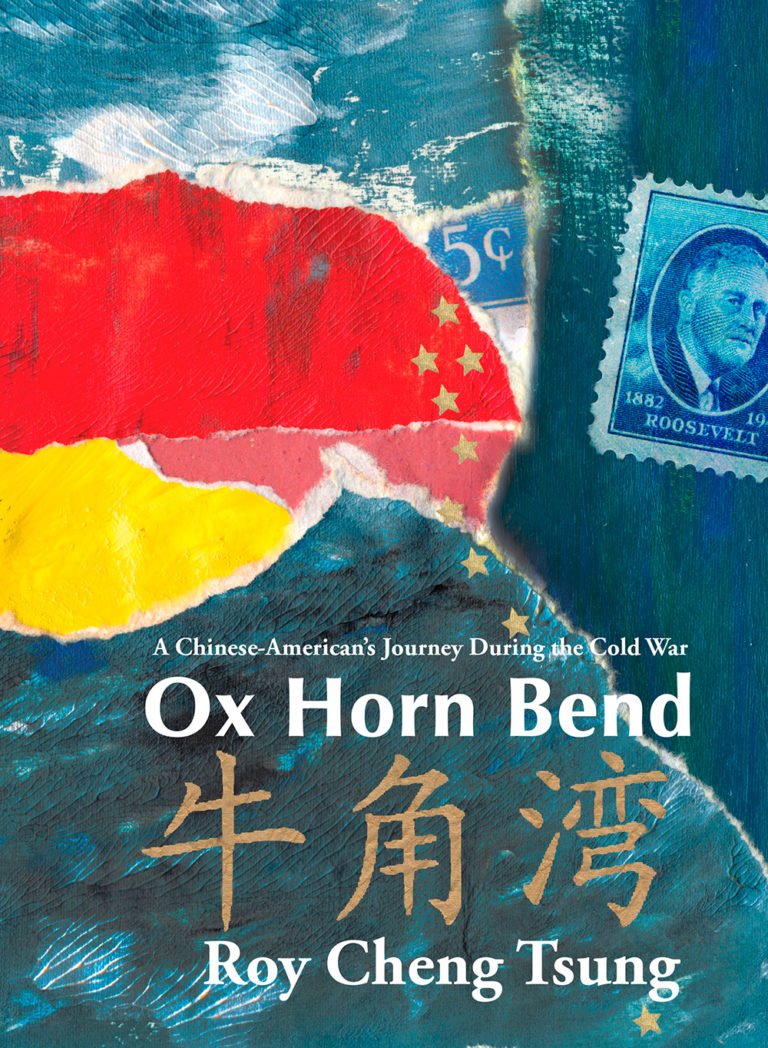

When Roy Cheng Tsung was a boy, his parents moved the family from New York, where Roy had been born, back to China because his father wanted to be part of Mao’s revolutionary new plan for his country. Suddenly, Roy was thrown into a very different culture, one in which political indoctrination and correctness was far more important than objective knowledge. Here’s a short excerpt from Roy’s book Beyond Lowu Bridge about finally finding a teacher that inspired him.

It occurred to me that Zheng Laoshi had never instructed his students to “put politics in command” or “be a red expert.” Chairman Mao was not in his vocabulary either. Instead, he talked about Galileo and Newton, Faraday and Maxwell, and their quest for science and the truth. It appealed to me as something that was pure and true, and far more admirable and noble than politics.

It happened to be the first anniversary of Sputnik I, humankind’s first artificial satellite to be placed into orbit; our class had bubbled with excitement when Zheng explained the significance. Instead of propaganda rhetoric about the great victory of Leninism, he drew parabolic curves and went into the physics of the satellite launch.

“You mentioned that if an animal were placed inside the orbiting satellite, it would be weightless,” I said to him. “How can that be?”

My teacher found a piece of paper and fumbled in his bag for a pen. “Don’t confuse body weight with body mass,” he said. Zheng jotted down some formulas and drew a picture of an orbiting satellite with a monkey on board. Plotting lines, curves and arrows, he explained how the animal lost its support force and entered a sustained state of weightlessness.

“This is what scientists call ‘zero gravity.'”

I scratched my head.

“Sometimes scientists need to use their imaginations,” Zheng chuckled. “Imagine yourself in the satellite. Both you and the satellite are actually in a continuous free fall around the earth, but never getting closer to the ground because the earth’s surface curves beneath you.” A little bulb lit up inside me as I remembered Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. I imagined myself with Alice, falling into the deep rabbit hole without any support force and feeling weightless.

Living in a totalitarian state where there was no freedom of thought, I was tired of listening to lecture after lecture by politically correct instructors who extolled Mao’s doctrines and rejected foreign ideas. But here was a young teacher who possessed something else. That something else was called “the quest for truth and knowledge.” I was fascinated.

That night, I went to bed with the happy thought that I had found a mentor.

An excerpt from Roy Cheng Tsung’s book Beyond Lowu Bridge.

Maureen Murphy Woodcock said, “I’m a modern Celtic woman. Before I learned to read and write, I listened to my Scottish, Welsh and Irish relatives as they sat around kitchen tables and told stories about themselves and our ancestors. It was a family sport. Who could tell the grandest tale! As my strange and amazing life unfolded, I kept my balance because I knew, just knew, that like my ancestors I had a whopping tale to share. It just took me more than a half a century to sort it all out.” Here’s an excerpt from Maureen’s piece “Japanese Blowfish and a Wooden Soo-Boy.”

Mr. Raney, my sophomore biology teacher, was an elegant man. He stood a couple of inches over six feet tall and, and though he was only in his forties, his hair was wavy and nearly white. His ears were flat against his head and his nose came out from his forehead at just the right Roman angle and length. His eyes were a vivid sparkling blue, and his teeth were slightly flawed – one of his incisors was crooked which made them real and naturally perfect. He seemed to have all the ingredients of an ideally created man. My love for Walter Raney wasn’t an easy infatuation. It was a love that required me to labor, to give him my best homework, my finest oral reports, my full attention, my adolescent academic soul. When I served him quality work, submitted polished reports as if they were sacred offerings, he sparkled. His blue eyes grabbed the light and flashed it back at me with a look that said, “Well done, young lady!” I was certain the muscles at the edges of his lips fought the temptation to brush my cheek before they changed directions and merely smiled at me.

That was an excerpt from “Japanese Blowfish and a Wooden Soo-Boy” by Maureen Murphy Woodcock from the Winter 2022 issue of Passager.

To buy Roy Cheng Tsung’s book Beyond Lowu Bridge, subscribe to, donate to, or learn more about Passager and its commitment to older writers, visit passagerbooks.com. Passager offers a 25% discount on the books and journal issues featured here on Burning Bright. Visit our website to see what’s on sale this week.

For Christine, Rosanne, Mary, Asher, and the rest of the Passager staff, I’m Jon Shorr.

Due to the limitations of online publishing, poems may not appear in their original formatting.