World Kindness Day

Recognizing the kindness of others, with poems from David Bergman, Henry Morgenthau III, and Rhett Watts.

TRANSCRIPT

November 13 is World Kindness Day. According to Wikipedia, its purpose is to overlook race, religion, and other boundaries and instead highlight good deeds in the community.

And speaking of community, Sunday, Nov. 16 is Passager’s Zoom Reading featuring people published in our latest issue. 2025 Passager Poet Angie Minkin and several 2025 honorable mentions will be reading their work. 2:00 Sunday Nov. 16. It’s free, but you need to register. Go to Passagerbooks.com, and click on “events” at the top of the page.

Back to World Kindness Day, David Bergman’s poem “The Man Who Fell Off the Curb.”

He was no angel or extra-terrestrial, but he plunged off

the curb so quickly he might have been Mulciber

hurled from heaven and into the waiting asphalt.

It was dark. It was rainy. He had just finished

dinner at the Korean diner at the end of the block. He

was not confused, just uncertain how much damage

he suffered. He made an inventory: front teeth

chipped, blood in his mouth, left rib cage bruised

badly, his right shoulder, which was giving him trouble all

day, was now giving him even more. All in all,

all right. Still he did not move. He felt like a statue

of a dictator deposed, a monument overthrown

to the cheers of the mob and their liberators. “Do

you think you can stand?” A woman, who stood

above and behind him, asked, her voice young and gladly not

maternal. “I’m all right,” he answered, but none too certain.

“We have to get him out of the street,” another unseen woman spoke,

and he saw that if there had been any traffic, he’d now be dead.

To his surprise, he began to get to his feet, a bit wobbly,

but needing less help righting himself than he feared. A man now

was speaking to the women, “I was making the turn and

saw him keel over, and I stopped as soon as I could.”

“The same thing happened to us,” said one of the women, the

one with the deeper more authoritative voice,

and unsteady as he was, he knew there was more than

one pick-up going on. The three of them gathered

his glasses, his book, his mobile phone

(they wouldn’t let him bend over) and put them

in his hand, one by one. He was being sent away like a child. “Do

you want us to walk you home?” one of them reluctantly asked.

“No, you’ve done enough already, and I live only a few doors down on

the other side of the street,” and then he remembered

he hadn’t thanked them. He hadn’t looked at them either. He’d

only heard them, and briefly, very briefly, felt their touch.

Well it was night and raining and his glasses were badly smudged.

“Thank you,” he said at last, and he tried to sound as sincere as he could.

“No need to thank us,” they answered together and laughed, and

he imagined they were thinking, “Poor old guy.”

He wanted to cry: I didn’t do anything to deserve this. I just got old. I

just got Parkinson’s, and I just fall. But he said nothing.

They watched him now as he waited for the light to turn green and

for him to slowly cross the avenue, and stand safely

on the opposite side of the street. When he turned to

wave back and thank them again,

they were already gone either to a bar nearby or

to their cars, and he knew

that even if one day he’d passed them, he’d not recognize their faces, nor

would they stop to ask how things had gone.

“The Man Who Fell Off the Curb,” David Bergman from his book Plain Sight.

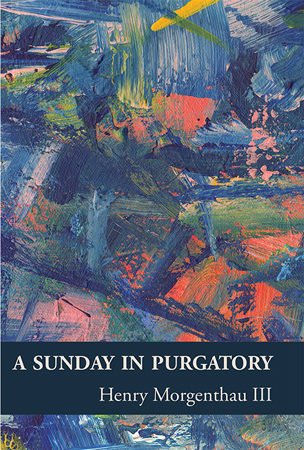

Next, Henry Morgenthau III’s poem “A Sunday in Purgatory.”

A voluntary inmate immured

in a last resort for seniors,

there are constant reminders,

the reaper is lurking around that corner.

I am at home, very much at home,

here at Ingleside at Rock Creek.

Distant three miles from my caring daughter.

At Ingleside, a faith-based community

for vintage Presbyterians, I am an old Jew.

But that’s another story.

I’m not complaining with so much I want to do,

doing it at my pace, slowly.

Anticipation of death is like looking for a new job.

Then suddenly on a Sunday,

talking recklessly while eating brunch,

a gristly piece of meat lodges in my throat.

I struggle for breath, too annoyed to be scared.

Someone pounds my back to no avail.

Out of nowhere, an alert pint-sized waiter

performs the Heimlich maneuver.

I don’t believe it will work.

It does! Uncorked, I am freed.

Looking up I see the concerned visage and

reversed collar of a retired Navy chaplain,

pinch hitting as God’s messenger for the day.

Had he come to perform the last rites,

to ease my passage from this world to the hereafter?

Don’t jump to dark conclusions.

In World War II on active duty,

he learned the Heimlich as well as the himmlisch.

Knowing it is best administered

to a standing victim,

he rushed to intervene.

On this day I am twice blessed

with the kindness of strangers.

From his book of the same name, A Sunday in Purgatory, Henry Morgenthau III.

We’ll end with Rhett Watts’s more personal poem about kindness from Passager’s Winter 2022 issue, “At Slack Tide.” It begins with the epigraph “the period of stillness just before the tide turns.”

Now that I no longer take long walks,

he brings me things

like the little green pinecone

he found in the woods.

It rests on my windowsill,

a placeholder for all that is

stunted and stunning.

He puts his jacket on and I say,

“Carry me with you, here,”

my hand on his breast pocket.

Smiling, he nods, then leaves.

Returns with tokens of the world:

a blue action figure fallen to the street

a nest blown from the eaves

of a barn he thinks he’d like to own

a stone so smooth

you could wear it in your shoe.

Once, when I was feeling utterly low,

he had me close my eyes

while he placed in my palm

a knobbed whelk shell. Washed up

onto the local mud flats,

its salmon-colored insides opened me.

“At Slack Tide,” Rhett Watts.

To buy, David Bergman’s book Plain Sight or Henry Morgenthau III’s A Sunday in Purgatory, to subscribe to, donate to, or learn more about Passager and its commitment to older writers, visit passagerbooks.com.

Passager offers a 25% discount on the books and journal issues featured here on Burning Bright. Visit our website to see what’s on sale this week.

For Christine, Rosanne, Mary, Asher, and the rest of the Passager staff, I’m Jon Shorr.

Due to the limitations of online publishing, poems may not appear in their original formatting.