Music

Two pieces sort of about music, by Donna Pucciani and Timothy Reilly.

6 minutes

TRANSCRIPT

Two pieces sort of about music. First “Two Chords and a Dog” by Donna Pucciani.

I love Khabib’s band, but after about half an hour

I have to bang my head on a lamppost

to let the two chords fall out.

The first time I heard him he nearly

blew my head off. It was at this little place

where the East Village borders Alphabet City.

He had on the usual tight black tee

and ripped jeans, carrying his acoustic guitar

on his back like an aging hippie,

his face leathered from the sun,

his eyes blurred from maybe staring at

too many naked light bulbs.

He had an old black dog with him, perhaps

a lab-shepherd mix, with the most liquidy

brown eyes I’ve ever seen, and this dog followed him

everywhere and sat at his feet as he played,

occasionally sending up an old-dog grumble

in the midst of chord changes,

yes, the same two chords, while Khabib improvised

a moaning chant in his hypnotic tenor. He refuses

to play where Percival is forbidden, but

at various museums or parks where

the Department of Health does not harass them,

the dog parks its shivering body at Khabib’s feet

and trembles in the vibrations and whatever

stinking breeze blows off the East River,

and together, their groans smoke up the stars

with the tarnished silver of music and devotion.

Donna Pucciani’s “Two Chords and a Dog” from Passager Issue 49. One literary critic said that “Pucciani is a poet of the sacred in the ordinary. [Her work] builds on the premise that what makes [people] holy is, in many ways, their very ordinariness.”

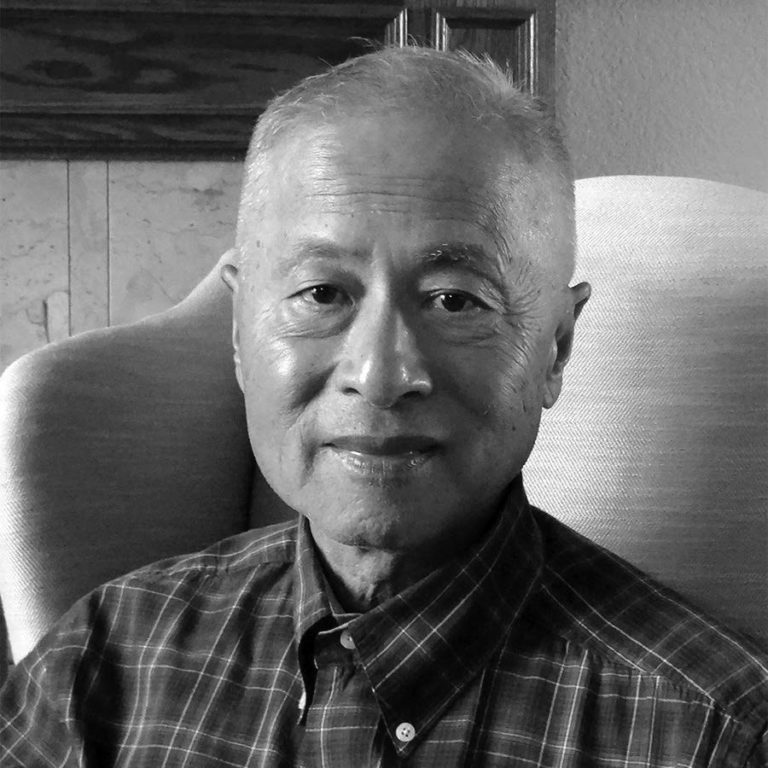

Timothy Reilly had been a professional tubaist until around 1980, when a condition called “Embouchure Dystonia” ended his music career. He said this story, “Down the Road,” came to him after reading his favorite parable about the Prodigal Son. Here’s an excerpt.

Head bent, I scurried along the curb, looking in the gutter for a small paper bag. . . . But instead, I discovered a clean, face-up copy of the tuba part to “Colonel Bogey March.” . . .

I sat down at the curb, reading the music. The bottom of the page listed copyrights of 1914 and 1941 (Hawkes & Son), and a 1958 arrangement copyright (Boosey & Hawkes). The cut-time march began in the key of B-flat major, shifted (at letter D) to the relative minor (g), returned to the opening melody, and ended with a trio in the subdominant key of E-flat major. The original composer (Kenneth J. Alford) and the arranger of the 1958 version (Clifford Barnes) were named in the upper right-hand corner. I noticed also that a beginner had penciled in a few “reminder” BB-flat tuba fingerings (1-2-3, for below-the-staff B-naturals; 2, for in-the-staff C-sharps; 2-3, for below-the-staff F-sharps).

It was strange enough to find sheet music abandoned in the gutter of the industrial area of a city. But it was even stranger that it was the tuba part for the very first ensemble piece I had performed, as a high school freshman, six or seven years ago. The fingerings might have been penciled by my own hand!

I recalled my high school band instructor telling us that “Colonel Bogey March” was not composed for the movie, The Bridge on the River Kwai. He said it was composed by a British army bandmaster, around the time of the First World War, and that it was inspired by an army colonel who loved to play golf. Apparently the colonel would not shout the customary FORE when teeing-off; he would instead whistle the descending interval of a minor third (the opening notes of “Colonel Bogey March”). My band instructor also said that the descending minor third is the same interval a mother uses to call a child in for dinner.

I thought about my first high school band concert. It was an amazing experience to be part of a large ensemble: performing music that excited an audience. I felt a sense of pride and accomplishment. I had worked hard to develop my musical talents. I had good sound and intonation, and performed with a keen sense of rhythm and the proper dynamics. My parents were proud of me. I wondered what they’d think of me now.

I looked down the road and saw in the distance the dim light from a Texaco sign. The rain was holding back but the sky was getting darker. I got up and began walking to the gas station, clutching the sheet music like a sacred scroll. The panic attack had been held at bay by the power of music. I whistled “Colonel Bogey.” . . .

An excerpt from Timothy Reilly’s story “Down the Road” from Passager Issue 62.

To subscribe to or learn more about Passager and its commitment to writers over 50, go to passagerbooks.com. You can download Burning Bright from Spotify, Apple and Google Podcasts, and various other podcast apps.

For Kendra, Mary, Christine, Rosanne, and the rest of the Passager staff, I’m Jon Shorr.