“I learned to nourish myself”

Conditions, cures and coping, featuring poems by Liz Abrams-Morley, Mary Jo Balistreri and Winifred Hughes.

7 minutes

TRANSCRIPT

November 7, 2024, marks the 157th birthday of Maria Sklodowska; most of us know her by a slightly different, married name: Madame Marie Curie. The Nobel Prize website says she championed the use of radiation in medicine and fundamentally changed our understanding of radioactivity. Madam Curie won the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics and the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, no slouch honor. She died when she was 66 of a condition she developed after years of exposure to radiation through her work.

At roughly the same time, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen won the 1901 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery—on November 8, 1895—of X-rays. One of his first x-ray images was his wife’s hand. When she saw it she said, “I have seen my death.”

X-rays. Radiation . . . To commemorate these two major advances in medicine and the people who discovered them, three pieces about conditions, afflictions, cures, and coping.

Liz Abrams-Morley said that her mother loved music, color, and nature; she taught Liz to engage the world, but kept much of her own past hidden. Liz said, “I spent my childhood constructing what I came to believe was her story.” Here’s Liz’s poem “My Doctor.”

My doctor prescribes potassium pills

Or, he says, a banana a day and I’m

seeing my long-dead mother

each time I reach for the fruit she taught me to eat

to settle a roiled stomach.

How often she’d say she was, herself,

allergic to bananas, though yellow,

the color of optimism, was the color

she craved each spring. Yellow forsythia,

yellow sun, yellow on a mild fruit she once called

toxic, my often silent mother.

Now yellow warblers blur past my streaked kitchen window,

a goldfinch dips, flies off. All gray winter:

Mother in her room, face to a white wall.

I learned to nourish myself.

From Passager’s 2010 Poetry Contest Issue, Liz Abrams-Morley’s poem “My Doctor.” Liz was the 2020 Passager Poet.

Mary Jo Balistreri said that in 2008, she had a cellular breakdown that affected every area of her brain and should have ended her life, but her friends, the “Grammas,” never lost hope. Mary Jo said she wrote “The Return” to celebrate that long-standing friendship and dedicated the poem to the Grammas.

We lean forward to fit into the camera’s lens, all seven

of us squashed together. Our weekly gathering

celebrates returns: of spring, of the snowbirds.

Of my own return from serious illness.

But standing in that spring field with my friends, the scarlet voice

of poppies screamed the sun’s too strong, and as I ran

my fingers gingerly over buttercups, I thought, they are not

as I remember. A nugget of fear lodged in my chest.

Months later as I look at my smiling face in the photo,

I recall how awkward that first get-together was for us all.

No one said anything except how good to have me back,

how good I looked. We were all adjusting to my croaky voice,

loss of hearing, of mobility. While some had returned

from vacation, I had returned from the dead.

I feel again the aloneness of that first excursion, how I was

a stranger to myself as well as to them; the tears shed

that I’d never be the same. It was true. I look no different

carry, like Persephone, indelible marks

from the underworld – caution and distance,

less certainty. Less energy.

But as I write this poem, I thank the Grammas:

Their cards that fill a book. The patchwork quilt

made for my homecoming from the ICU, each square,

an individual hand imprinted within. A wall hanging

in my bedroom now, I look to those hands,

wake to them yet, each morning.

Mary Jo Balistreri’s poem “The Return” also from Passager Issue 50, the 2010 Poetry Contest Issue.

Winifred Hughes said that when we write about things from our past, we reanimate them and make them new again. Here she is writing about an event she missed: “In Early March.”

I missed her dying.

How could I not have been there

after so many days of watching

at her bedside, reading poem

after poem as though words

could have something to do

with this shutting down, as though

silence needed words to contain it,

as though words might be breath?

Someone else heard the last, someone

else touched his hand to her eyes,

while I had gone from the books

that she loved into the raw poem

of the marsh at dusk in the last

of winter to see the clumps of reeds

dissolving into mist, the slice of sky

holding out against encroaching

extinction, and the small bodies

of woodcocks launching themselves

into that lowering remnant of sky.

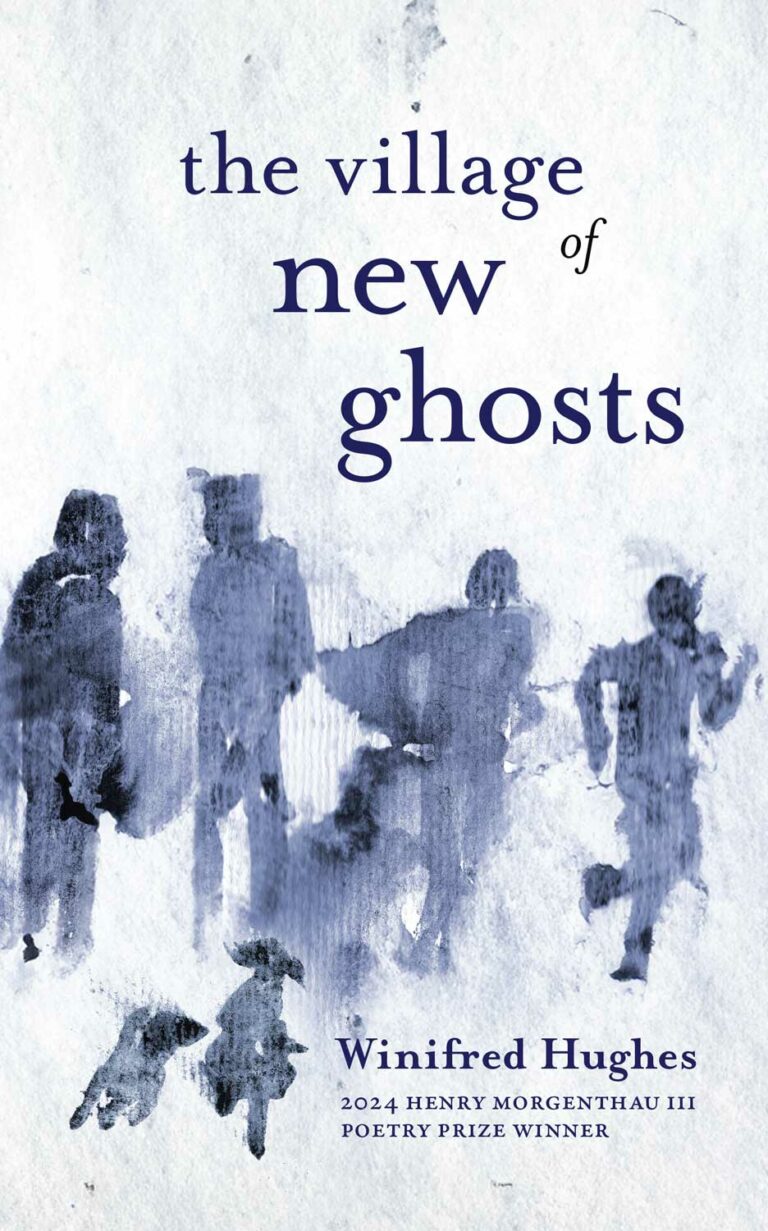

Winifred Hughes’s poem “In Early March” from her brand new book The Village of New Ghosts.

To buy Winnie’s book, subscribe to, or learn more about Passager and its commitment to writers over 50, go to passagerbooks.com. You can download Burning Bright from Spotify, Apple and Google Podcasts, and various other podcast apps. Passager offers a 25% discount on the books and journal issues featured here on Burning Bright. Visit our website to see what’s on sale this week.

For Kendra, Mary, Christine, Rosanne, and the rest of the Passager staff, I’m Jon Shorr.