Veterans Day

The personal impacts of war, featuring poems by Judith Slater, Winifred Hughes, James McGrath and Michael Miller.

7 minutes

TRANSCRIPT

In 1982, Nov. 13 was Veterans Day. And that was the day the Vietnam War Veterans Memorial

was dedicated. According to the Department of Defense’s web site, it’s the most-visited memorial on the National Mall in Washington. The most prominent feature on the two acre site is a massive wall that lists the names of the more than 58,000 servicemen and women who lost their lives during the Vietnam War. On this episode of Burning Bright, five pieces about war and veterans.

Judith Slater was seven when WWII ended. She said, “We did not get a daily paper

or listen to nightly news. My awareness that our soldiers were being killed came during infrequent visits to my grandparents.” Here’s her poem “Personal History.”

When I shocked a college friend with my ignorance

about the war, I tried to explain my small town.

The friend’s father helped liberate Buchenwald,

my father, too old for the draft, volunteered

for civil defense, bringing back stories — a report

of “an enemy submarine” that turned out to be

the Goodyear blimp. For kids, helping

the war effort involved making foil balls

from gum wrappers and flattening tin cans.

I sat beside my grandfather when he tuned

his Philco to the nightly news about battles

in places that sounded like melodies —

Singapore, Okinawa, Corregidor, Saipan.

Then I’d try to cheer him by picking out tunes

from sheet music about love and laughter and peace

ever after, Tomorrow, when the world is free.

Judith Slater’s poem “Personal History” from Passager Issue 71.

This next poem is also about a child who lives through a war, but in this case,

the war was much closer. “My Mother’s Oranges,” Winifred Hughes.

A little girl in England after the war

ate twenty-seven small oranges

from a wooden crate that had

found its way to her parents’ door

amid the loss and the aftermath.

After the years of drinking blue milk,

and no butter, she couldn’t stop eating

until she was sick, couldn’t stop tearing

the bittersweet fruit that the animal

inside her instinctively devoured.

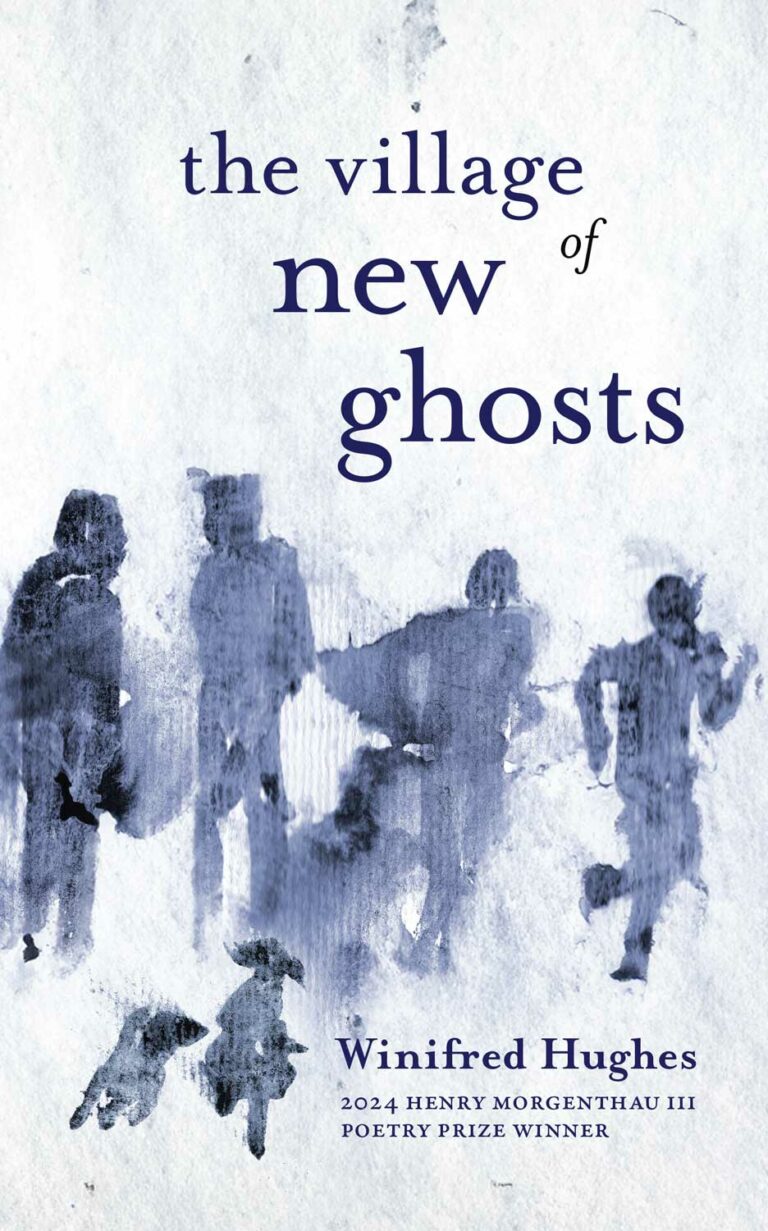

“My Mother’s Oranges,” Winifred Hughes from her book The Village of New Ghosts.

James McGrath worked for the U.S. State Department as a poet-artist in residence

in Yemen and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Here’s a war veteran poem he wrote,

“My Winter Soldier.”

My brother played drums in his high school band.

He sang Bacharach songs to Fatima down the road.

He tickled my mother with a peacock feather.

He laughed at my 4th grade elephant jokes.

He teased Dad about his bright ties.

My brother came home last week from Iraq.

He wore a piece of shrapnel from his shoulder

on a chain around his neck.

He had a prosthetic arm with five plastic fingers

in a white glove.

He called Dad a motherfucker because he wore

a tie.

He said he had shot elephants and peacocks

in the Baghdad zoo for target practice

with his buddies.

He said Fatima was just another stupid Hajji.

He sold his drums on e-bay.

Last night at dinner he told us how they poured

gasoline on a library in Fallujah, shooting

into the shadows until they ran red.

How the books burned, even Rumi couldn’t escape

the flames.

He cried in his room all night, tossed grenades

of four-letter words into the dark.

This morning he never came down to breakfast.

“My Winter Soldier,” James McGrath. James was the 2015 Passager Poet.

Michael Miller served four years as a Marine. Here’s a poem titled “Character”

from his book The Solitude of Memory.

Before the sniper fired,

His face was handsome.

Now his wife says

It has character

As she kisses the scar.

The bullet came out of the rocks,

And Ortiz, the cigarette

Between his lips, went rigid

When it entered his temple,

Came out his ear,

And slashed Eric’s cheek.

He buried his Purple Heart

Beneath the pear tree

In the garden,

Where he smokes after dinner

For Roberto Ortiz.

Michael Miller’s poem “Character.” We’ll end with another of Michael’s poems,

“Comrades.”

Something inside him winced

At the word Vietnam

Where he kissed a bar girl

For luck before every patrol:

Ambushes, fire-fights,

The bodies of comrades

In bloody pieces.

On his forearm the tattoo:

DEATH BEFORE DISHONOR.

Fishing and hunting

In the Blue Ridge Mountains

Were his medication,

Whiskey on the porch

With Johnny Cash

Singing as he dozed.

Two marriages failed

Before solitude became

His trusted comrade.

Michael Miller’s poem “Comrades,” also from his book The Solitude of Memory.

I said earlier that 58,000 Americans died in Vietnam. But that was less than one-tenth of the number that died during the American Civil War—620,000 Americans—ten times the number that died in Vietnam. Reminds me of that old line, attributed to comedian George Carlin, “Bombing for peace is like screwing for virginity”—(he didn’t use the word “screwing.”)

To buy Michael Miller’s book The Solitude of Memory, Winifred Hughes’s brand-spankin’ new book The Village of New Ghosts, subscribe to or learn more about Passager and its commitment to writers over 50, go to passagerbooks.com. You can download Burning Bright from Spotify, Apple and Google Podcasts, and various other podcast apps. Passager offers a 25% discount on the books and journal issues featured here on Burning Bright. Visit our website to see what’s on sale this week.

For Kendra, Mary, Christine, Rosanne, and the rest of the Passager staff, I’m Jon Shorr.

Due to the limitations of online publishing, poems may not appear in their original formatting.